You have to work to locate artist Charles Burwell—by stepping gingerly across a junk-strewn lot, pushing open an institutional pink door, pulling open an imposing set of black doors, skipping up a few makeshift wooden stairs, and then walking through the final entrance into his 2,700-squarefoot Kensington studio. Getting to the heart of Burwell’s paintings isn’t easy, either. “A lot of my work has something to do with not being able to push your way through,” he says. “And there’s certainly a connection to my living and working in Philadelphia with all of its visual complexity. I’ve always been interested in early modernists whose work reflected that kind of urban energy.” A particular favorite, he says, is Fernand Léger’s The City at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

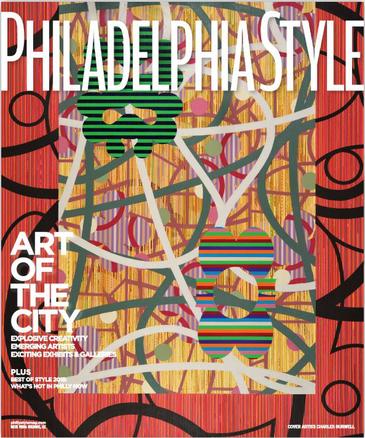

A faint aroma of stale smoke hangs in the air, and African music plays softly in the background. Burwell, 60, crouches near the bottom of an enormous canvas, meticulously painting black squiggles. Crimson is the dominant shade of this abstract, but the original background has been subsequently overlaid with amorphic shapes striated by tones of emerald and olive, navy and lavender; elsewhere, crystalline spheres of teal and peridot bounce through a swirling trail of aubergine. The effect is that of a Pollock meeting a Matisse cutout, with sprinklings of styles like Color Field, Op Art, and Pop Art. Its precise chaos is all Burwell, though, a distinctive mélange of lines, drips, and geometric forms that are often inspired by the organic shapes found in nature. Or not. When a viewer points toward one blob and says it resembles Snoopy, Burwell offers a different cartoon figure: Tweety.

“I have to remember to maintain a sense of play. I’m ready to be a bit more spontaneous.” —Charles Burwell

Unfurling his lanky body, Burwell rises to his full height of 6-foot-4 and wipes his hands on his overalls, which are already spattered with paint. From the assortment of mismatched furniture that litters the sprawling space, he plucks an incongruously small and feminine upholstered chair and settles in, gesturing toward the work he and an assistant are currently finishing. It’s his largest ever, he says—clocking in at 19 feet by eight feet—before describing how it’s all come together. “This piece began as a row of free-form stripes painted on by brush,” he explains. “Then it became a layering process where the stripes were followed by a series of shapes, then a series of drips. Each layer obscures what’s underneath— that’s what I want.”

He started working on this latest piece, called Red Frequency, last year, using, as a jumping-off point, what seems to be all available hues of the color red. Eventually, it will have more than a dozen layers. “I’m not sure how I define ‘complete,’” he says. “At a certain point, it offers a feeling of completeness, that’s all. Lately, I’ve been leaning toward an excess of information, so the paintings are getting more complex.” It “takes a certain kind of personality to live with that intensity,” Burwell adds, allowing a touch of wryness to enter his otherwise measured tones.

But complete it he must, since this particular work will be installed at the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts in Wilmington, where it will serve as a focal point for an exhibit called “Layering Constructs” (on view through September 7). In addition to Burwell, the show is displaying works by Margo Allman and Antonio Puri, two other abstract artists who use layering; a joint exhibit will be presented concurrently at the Delaware Art Museum (through August 2).

Thanks to the increasing complexity of his work, the hometown artist is enjoying a recent breakout in his career. Burwell is selling more and more outside of Philly, is having his shows reviewed in the art world’s leading publications, and is contributing to major exhibitions, including a recent run in a traveling show at the renowned McNay Art Museum, in San Antonio, Texas, and the Akron Art Museum, in Ohio.

“Charles has had an incredible two years,” says Bridgette Mayer, owner of the eponymous Bridgette Mayer Gallery, on Washington Square, who represents Burwell locally. “Collectors love Charles for his use of color and the intricacy of his processes.” Indeed, Burwell has begun to attract collectors’ eyes so much that Mayer featured his work in her gallery’s booth at the Art Miami art fair, which runs during Art Basel Miami Beach, this past December. It was the fifth consecutive year the artist’s work had traveled south for the winter.

Burwell grew up in West Philadelphia and took Saturday art classes as an elementary school student followed by classes at Moore College of Art and Design while in high school. “If these opportunities weren’t available when I was young, I don’t know that I would have gravitated toward art as a career,” he says. He went on to attend the Tyler School of Art before pursuing an MFA degree at Yale University School of Art, where he studied with influential modernists like Elizabeth Murray and William Bailey. “There’s a legacy and a weight of teaching art history at Yale that parallels the development of contemporary art,” he says now, thinking back to the time he spent there in the 1970s. “It sort of hangs over your head—I felt myself constantly asking how I fit in. In the end, it means very little once you’re in your studio. It means practically nothing.”

He needed to discover his own style, and did so by looking at art and then looking some more. On a trip to the Freer Gallery of Art, in DC, he was impressed by how ancient East Asian art could seem so modern, distilled as it is into a series of gestures, “of marks on the page rather than representative forms,” he says. “It changed how I thought about art. From then on, much of my work was about making my own ‘mark.’ In the last few years, I’ve gotten away from that, but it’s still there, mostly represented by the drip.”

The drips, however, are subtle. What emerges as Burwell’s true signature is his ongoing exploration of geometric shapes. Over the years, he has created hundreds and hundreds of templates, first by hand and in the last decade or so by computer. “It’s sort of a vocabulary I’ve developed,” he says. There are straight-on circles, ovals, and geodes, but also more amorphous forms that look like clouds, thought balloons, toy jacks, jigsaw puzzle pieces, or teddy bears. Once Burwell or an assistant traces a template onto the canvas, it’s time to painstakingly fill it in. It’s here that Burwell’s fondness for stripes, dots, grids, diamonds, and plaids is given life. It sounds like a mad jumble, but each work is tightly constructed and symmetrical—there is never any sense of sloppiness or of something missing.

“Part of my personality is that whatever I do, there is going to be an implied sense of order,” Burwell says. “It’s me trying to figure out where things are supposed to be. When I start, I have no idea how, or if, it’s going to work. Sometimes I’m surprised when it does.” If it all gels, he says, there’s logic to the space, the range of colors, and the interaction of the forms. “There’s a kind of believability that’s guided by the history of art and my own desires in terms of the place I’m trying to arrive at.”

“Whatever I do, there is going to be an implied sense of order. It’s me figuring out where things are supposed to be.” —Charles Burwell

His path to the place he’s in now has been filled with a panoply of fellowships and grants, and he’s enjoyed residencies at a series of art colleges up and down the East Coast. He’s taught mural arts to kids in Wilmington and has been a visiting lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design. He’s exhibited steadily since graduating from Yale in 1979, and his work can be found in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the African American Museum in Philadelphia, the Delaware Art Museum, and the Studio Museum in Harlem, in New York City. The Philadelphia Museum of Art showcased two major paintings of his just this January as part of the show “Represent: 200 Years of African American Art.”

Living and working in Philadelphia “has worked well for me over the years,” says Burwell. He adds that many young artists are forging a similar path. “Art school graduates are choosing to stay in Philadelphia rather than go off to New York. Some have formed artist collectives as an alternative to the commercial scene, and as a way to show their own work and the work of their colleagues,” he says. “There is an energy in Philly that’s generated by these young artists that’s not gone unnoticed by the larger art world. A number of articles have appeared in The New York Times and art publications about the Philly art scene. The Barnes, the Art Museum, and Institute of Contemporary Art, all world-class institutions, are getting more national media coverage, which makes the city a competitive art world destination.”

Burwell has enjoyed more than 30 years in the business, but there have been challenges, too. “The day-to-day work in the studio is always a laborious process,” he notes. “I’ve wanted to be an artist since I was in grade school, and there have been difficult times over the years trying to remain a full-time artist. But I suppose I was too stubborn to give up.” Still, Burwell seems eager to mix things up a bit. “I have to remember to maintain a sense of play, to carve out time for that,” he says. “I’ve been spending a lot of time on these large, very planned paintings. I’m ready to be a bit more spontaneous. I’m thinking that I’ll start working on some smaller pieces…. I can see interesting possibilities for where the work will go.”

- Philadelphia Style Magazine