Damian Stamer "Visual Spaces"

by Daniel Tidwell

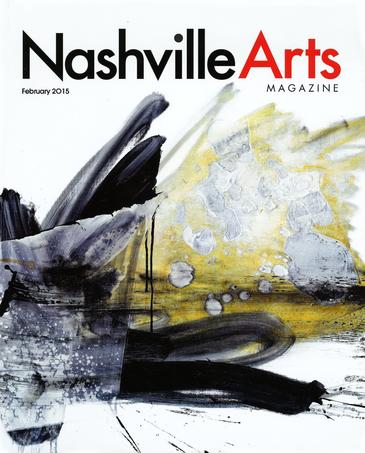

Damian Stamer’s paintings are multilayered meditations on memory, loss, nostalgia, and sentimentality. Heavily worked, rich surfaces yield clues to the history contained in images of abandoned buildings and rural landscapes. In his most recent work, the structures and fields of his native North Carolina are often engulfed in a whirl of broad, gestural strokes—obscuring the images while evoking the effect of time’s passage on a rapidly fading memory.

As a child in North Carolina, Stamer often explored the deserted structures and fields near his home. “These are the same old barns, relatively unchanged, that my bus passed every day to and from school over twenty years ago,” says the artist. Maintaining a connect to the landscape of his youth is important to Stamer, and so he splits his time between studios in Brooklyn and Hillsborough, North Carolina, where he photographs the structural elements that become the basis for his paintings.

Stamer’s photographic library from the region now contains thousands of images from which he paints. “The only exception to date,” according to the artist, “is my use of Dorothea Lange’s photographs housed at the Library of Congress. In 1939, Lange visited Person County—a stone’s throw from the places I paint—to document the tobacco workers on behalf of the Farm Security Administration. Although time separates me from her images, I feel a kinship to both the artist and these sites by furthering their stories in paint.”

Conceptually, Stamer’s work strikes a balance between the intuitive and the theoretical, relying heavily on the evolution of the image through his mark-making process. One concept that figures heavily into his work is the German idea of Heimat, or homeland, and the notion of how one is deeply connected to the land in which one was born and raised. Growing out of that concept are issues of regional taste and sophistication and how less urbane aesthetics are perceived by “a predominantly urban-centric art world.” For Stamer, “The simple act of making my work, alone in the studio, through a relationship with humble materials, displays a decided politics of creation—one that contrasts sharply with other modes of artistic production found today.”

While Stamer engages with concepts such as these that connect his work to a broader critical and theoretical conversation, he states that he is “mostly a formalist at heart.” The images lurking beneath his paint surfaces are his painting’s skeletons and the springboard for his process. “There comes a time when these biographical and identity-laden concerns fall away, like the rockets of a space shuttle after launch. Chance and intuition take over. Painting becomes a dance outside the realm of language and concept.

“My most exciting times in the studio come when I discover how to make a new mark or surface effect,” says the artist. “I’m like a scientist, always tinkering and experimenting with unique ways to push my medium. When I find a new way to use paint that I’ve never seen before, I feel like I am adding to a conversation that began thousands of years ago.”

A good example of the balance Stamer strikes between formal and conceptual approaches can be seen in the evolution of a predominately monochrome color palette used in much of his work from the past two years. According to Stamer, the monochromes developed partly out of his desire to better highlight newly developed marks and surface treatments. Conceptually the use of monochrome also lent itself to his central themes of memory and loss—referencing “the difficulty of accessing information and emotions of years past, translated visually through faded colors and erasure.” Stamer says that “these works also hinted at black-and-white photography, perhaps our most common window to the past, with white borders and dappled aging.”

Anselm Kiefer’s monumental depictions of historically loaded landscapes and interiors have been an important influence on Stamer’s work, as has the work of Matthias Weischer, Neo Rauch, and Gerhard Richter. Other older influences that Stamer cites include Robert Rauschenberg, Willem de Kooning, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andrew Wyeth, and Édouard Manet.

Stamer says that showing his work in New York has not necessarily affected its development; however he does feel that living there has had an overall positive impact on the path of his painting. “New York has a unique energy and hustle. Combining this vitality with the number of galleries, museums, artists, and overall brilliant thinkers New York has to offer provides an ideal atmosphere to push my work.”